Bodily Autonomy

Masculinities and Changing Conceptions of Manhood in Colonial America

“When asked by Captain Nathaniel Bass, Warrosquyoacke's most prominent resident) "whether he were man or woman," Hall replied that he was both. Confounded by the discrepancy between Hall's purported male identity and his appearance, another man inquired why he wore women's clothes. Hall answered, ‘I go in woman’s apparel to get a bit for my Cat.’"

Masculinities

What it means to be a “man” will vary across culture, class, and ethnicity. Ideals of manliness also change over time.

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, roles, and relationships of power associated with men, boys, transmen, and lesbian butches as well as other two spirit and third gender roles.

The definition of masculinity is historically specific, and it changes. As we saw in comparing the performance of strength by political figures like Kamala Harris, Donald Trump, Tim Walz, and JD Vance, there are competing ideals of masculinity in our present.

Women can also perform masculinity: as in the 2024 Presidential Debate and at the DNC when Harris presented herself as potential commander in chief.

Make Present Day Masculinities Strange

As queer approaches to history can show, study of the past can make the past familiar and the present strange.

When historicized, seemingly “natural” qualities are proven to be cultural constructs, fictions, and performances of gender within a normative gender system specific to time and culture. By familiarizing ourselves with alternative gender systems, like that of the Wampanoag in 17th C New England or the Euro-American farmer in animistic relation with land, we can also see the strangeness of our current, dominant gender ideology, and present day norms and ideals for masculinity.

Although we live in the same patriarchy brought to the Americas by colonial settlers from Christian Europe in the 17th C, looking at masculinity and bodily autonomy in Colonial New England and Colonial Virginia, reveals historical change. We can also see the strangeness of today’s American masculinity in contrast with Indigenous gender ideologies, such as the story of Skywoman and the story of Weetamoo/Namumpum and Ousamequin/Massasoit.

As Brooks taught us, Ousamequin engaged with English patriarchy by supporting Namumpum’s sovereignty over her land despite the difficulty English men had in recognizing that. He also allowed Englishman Edward Winslow to cure him of thrush, very intimately.

This week, we are looking at bodily autonomy in confrontation with normative frameworks for defining relations with land and the body of a transgender person in 17th and 18th C colonial America.

Bodily Autonomy, Manhood, and Land Relations

First, reading Carolyn Merchant’s chapter, we considered the changing relationship with land in European “Old World” and the New England “New world.”

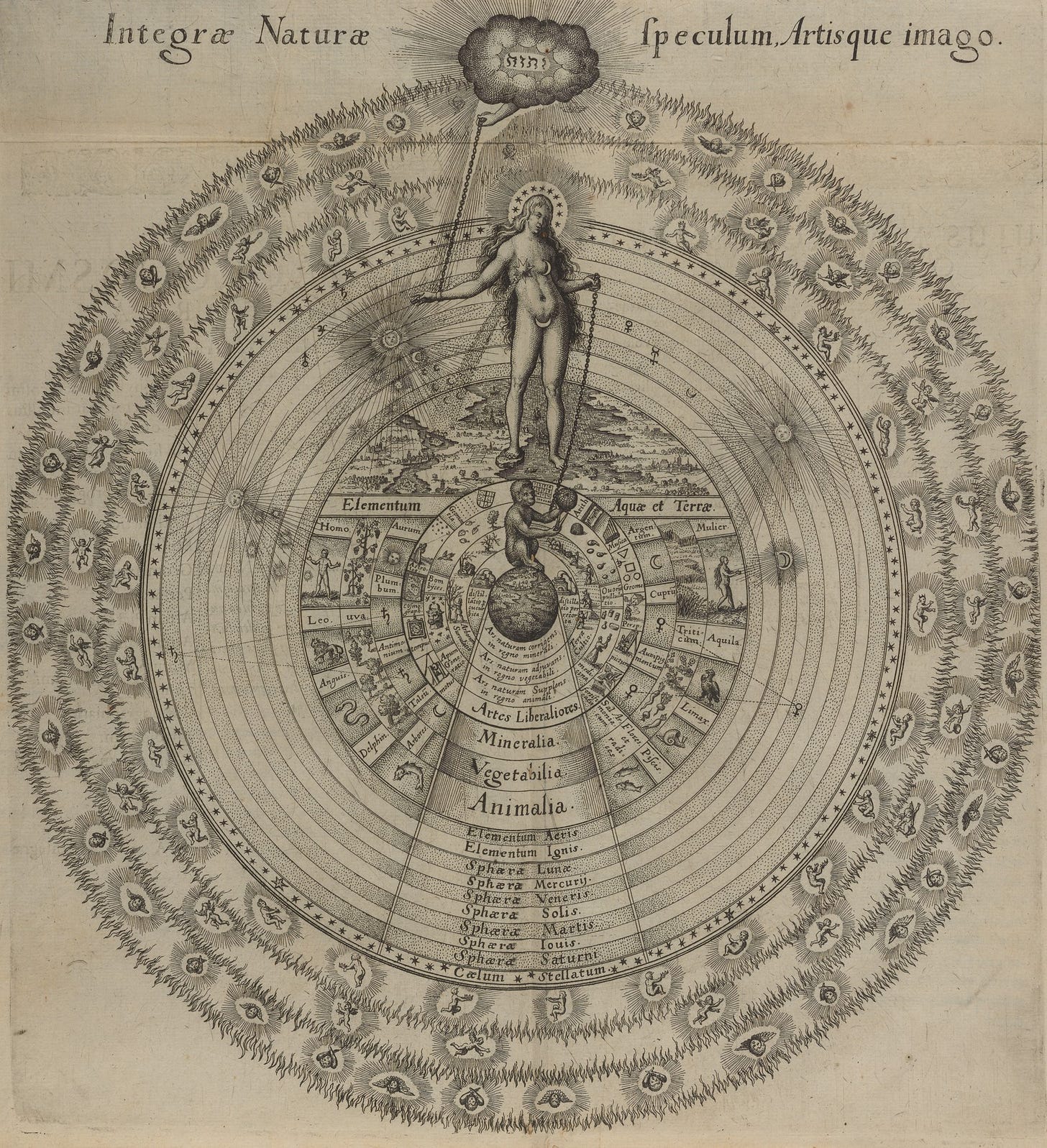

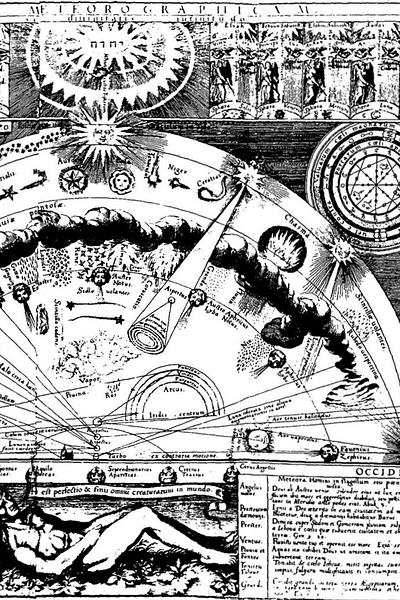

Merchant describes the shift from animism, in which everything is imbued with spirit, to the mechanistic worldview, where everything is a machine created by God as mathematician. We also briefly saw how religious ideas changed, from Puritan wilderness fears to the ideas of the 18th C Great Awakening, which celebrated land as their god’s loving gift. In the process of mechanization, Mother Earth was objectified and represented as a thing. This also changed relationship with land is reflected in changed dynamcis between men and women and with those relations, ideals of masculinity.

How does the definition of manhood through relationship, especially relationships of dominance, make men and male identities, dependent on women’s submission and, thus, vulnerable and fragile? What is an example of this?

We see patriarchy in all three of these relationships and also changing. How so? How is God a part of patriarchal models? How does patriarchy go back to Adam and Eve? What was Adam’s role and how does it relate to the role of the colonial farmer and the scientists in the 17th and 18th C Atlantic World.

How do these relations compare with Skywoman and the Wampanoag idea of kinship with the land and responsibility to the land in Native American relations of sovereignty?

When the land is objectified and becomes a thing, what does it become possible for colonial farmers and as capitalism and industry advance, for Anglo Americans to do to the land?

In the mechanistic model, there is a step in which nature is rushed. How do humans use technology to rush nature? What technologies are they using? What is the thinking of Bacon and then Descartes, that facilitates this rushing and objectification of nature?

Interesting to note: gender history has made much of the different timing of men and women, timing in the bedroom was modelled on the different demands and timing of home and factory or domestic and public space. However, with farming, men and women typically worked side by side as a family unit. In Colonial New England, women at times took on the role of "deputy husband," meaning they stepped in to do the work of the husband when he was called away from the farm.

In relationship to the land, as we saw in the Brooks reading, what is husbandry? What does it mean to husband the land? What would it mean for a woman to husband the land? Is that a performance of masculinity by a woman?

How does husbandry change with mechanization ? Do people stop thinking of themselves as husbands when land becomes an object, a dead thing, a machine? Or, does what it mean to be a husband and thus a man in relation to a woman partner change?

Bodily Autonomy - Further Thoughts

Returning to the question of bodily autonomy, who has it? Men, women, land? Who loses it? How does the land's bodily autonomy relate to the bodily autonomy of women? As Kimmerer reminds us, it is never that humans don't take from the land and reciprocate in ritual and in their waste and eventually death and decay.

It might be interesting to note that in other work, Merchant connects Bacon’s mechanistic idea of nature as a thing, to be tortured for information and rushed to fruition as connected to witch hunts. Unruly women were like unruly land, needing domination and discipline.

In further considering ideals of masculinity, dominance, and relations to land, consider relations BETWEEN men. Hierarchies of class and labor relations put men in relations of power with each other that are gendered. Often workers are more physical, bosses more aristocratic. So workers can claim manhood as strong bodies, but elite men dominate them still.

Then, these gendered relations of power get racialized in slavery. How so?

To connect labor relations to relations with land, Martin Heidegger argued that framing land as a thing from which value can be extracted or is he puts it “challenged fourth,” also frames all humans, especially working people, as things who are in feminine relationship with a minority of socially economically and politically empowered men.

Think about how in this election, reporting suggests that white men who might benefit more from the pro-union platform of Harris are still inclined to support Trump, who clearly represents the economic interests of empowered elite, like Elon Musk.

We see how gender comes into play amongst people of color, with claims that black and Latinx men are more inclined to value and trust Donald Trump because subjecting themselves to a woman president might be emasculating. Across race, some men have looked up to Donald Trump because he can say whatever he wants and get away with anything.

How might the politics of objectification and the surrender of bodily autonomy along the American gendered hierarchy explain some of the race and class dynamics in this election?

Bodily Autonomy: the Case of Thomas/Thomasine Hall

Turning to the Colonial Virginia case of Thomas/Thomasine Hall, the primary source tells us a story of a person who identified as both male and female and moved seemingly easily between genders without being challenged. Hall lived a long time with bodily autonomy enough to move between both genders in England before moving to Colonial Virginia, where reports surfaced that Hall had engaged in illicit sexual behavior that was legally considered fornication.

As historian Kathleen Brown summarizes:

“Hall soon became the subject of rumors concerning his sexual identity and behavior. A servant man's report that Hall "had layen with a mayd of Mr. Richard Bennetts" may initially have sparked the inquiry that led to questions about Hall's sex. Although fornication was not an unusual offense in the colony-the skewed sex ratio of nearly three men to every one woman and the absence of effective means for restraining servants' sexual activities produced a bastardy rate significantly higher than that in England’s. Hall's response to the charge and the subsequent behavior of his neighbors were quite out of the ordinary. When allegations of sexual misconduct and ambiguous sexual identity reached the ears of several married women, Hall's case spiraled into a unique community-wide investigation that eventually crossed the river to the colony's General Court at Jamestown.

“Court testimony revealed that while in England, Hall had worn women's clothing and performed traditionally female tasks such as needlework and lace making. Once in Virginia, Hall also occasionally donned female garb, a practice that confused neighbors, masters, and plantation captains about his social and sexual identity. When asked by Captain Nathaniel Bass, Warrosquyoacke's most prominent resident) "whether he were man or woeman," Hall replied that he was both. Confounded by the discrepancy between Hall's purported male identity and his appearance, another man inquired why he wore women's clothes. Hall an- swered, "I goe in wcomans aparell to gett a bitt for my Catt." As rumors continued to circulate, Hall's current master John Atkins remained unsure of his new servant's sex. But the certainty that Hall had perpetrated a great wrong against the residents of Warrosquyoacke with his unusual sartorial style led Atkins to approach Captairl Bass, "desir[ing] that hee [Hall] might be punished for his abuse."”

As a result of these questions, Hall’s body was examined three times.

“The first to lay hands on Hall for the purposes of gathering information was a group of women whose interest had been piqued by a “report" that Hall was both a man and a woman. Groups of women usually searched only other women at the request of a local court; their authority to glean information from bodies rarely crossed gender lines and they did not usually initiate a search without the backing of local officials. With Hall's then-master, John Tyos, claiming his servant was female, however, the women decided that it was appropriate to intervene. Searching Hall's person for evidence of his sexual identity, Alice Long, Dorothy Rodes, and a third woman, Barbara Hall, concluded that "hee was a man."”

Still questions persisted.

“Despite this new evidence, Master Tyos continued to swear to Hall's female identity, provoking John Atkins, who was contemplating the purclwase of Hall, to take the problem to plantation commander Captain Bass. Confronted with the array of conflicting evidence the rumors of Hall's hermaphroditism and alleged fornication, Hall's master's claim that his servant was a woman, and the married women's findings that he was male Bass asked Hall point-blank ;'whether hee were man or woeman." Hall answered that he was both, explaining that although he had what appeared to be a very small penis ("a peece of flesh growing at the . . . belly as bigg as the topp of his little finger [an] inch long"), "hee had not the use ofthe man's p[ar]te." Hearing this confession, Bass ordered Hall to put on women’s clothes. Although difficult to prove in court, male impotence was considered sufficient grounds for the annulment of marriages; it became for Bass, in this instance, a sufficient condition for determining female gender identity.”

Doubts about this conclusion led to a second search.

“Bass's decision did not sit well with the group of married women who claimed to have seen evidence of Hall's manhood. But with Hall parad- ing about Warrosquyoacke in the mandated female attire, they also be- gan to "doubte of what they had formerly affirmed." Trooping over to Hall's residence at the home of his new master, John Atkins, the group searched the female-clad Hall while he slept, confirming their original judgment that he was a man. In an unusual breech of etiquette, more- over, they insisted that Master Atkins view the proof for himself. Atkins tiptoed to Hall's bed but lost his nerve when '4shee" stirred in her sleep. So convincing a woman was Hall that Atlrins abandoned the idea of un- dressing the sleeping servant. In subsequent descriptions of this incident before the General Court, Atkins found it impossible to describe Hall with other than female pronouns.”

Then a third search was done.

“Tenacious in their quest to reveal the "truth" to Atkins and to two other women who had joined their ranks and perhaps still harboring doubts themselves-the married women planned a third search of Hall's person. When Atluns finally saw the evidence of Hall's manhood he was unimpressed and asked Hall "if that were all hee had." Perhaps Atkins, like Hall himself, doubted the significance of the small "peece of flesh" protruding from Hall's belly and wondered whether there might be other anatomical clues. Describing his identity for the first time as the presence of female anatomy rather than as a lack or deformity of male- ness, Hall told AtlQins that he had "a peece of an hole." AtlQins immedi- ately insisted that Hall lie down and "shew" these female credentials. After searching together in vain for Hall's vagina, Atkins and the married women concluded that Hall could not be a hermaphrodite. Although Hall's penis may have been tiny and in poor working order, it became for Atkins and the matrons, in the absence of other "evidence" of female- ness, the dominant criterion for Hall's social identity. In sharp contrast to the language Hall used to describe his own freewheeling sense of chosen identities, Atkins ordered Hall to "bee put into" male apparel and urged Captain Bass to punish him for his "abuse.'”

And yet, there would be a fourth search.

“As soon as Captain Bass reversed his decision about Hall's gender identity and proclaimed him to be a man, Hall became fair game for the men of Warrosquyoacke. Hearing a "rumor and report" of Hall's tryst with Mr. Richard Bennett's maid Great Besse, Francis England and Roger Rodes took advantage of a chance meeting with Hall to conduct their own impromptu illvestigation. Rodes declared, "Hall thou hast beene reported to be a woman and now thou art p[ro]ved to bee a man, I will see what thou carriest." Assisted by England, Rodes threw Hall onto his back. England later told the General Court that when he "felt the said Hall and pulled out his members," he found him to be "a per- fect man."”

Hall is then taken to the Court in Jamestown and examined in the court of law, on the stand. That record is the document we read.

As Kathleen Brown and the court record show, the verdict is that Hall is indeed both man and woman. The punishment was to have this displayed always, through prescribed clothing.

“Their order that the male-clad Hall should mark his head and lap with female accessories-"a Coyfe and Croscloth with an Apron before him" -attested to their power to punish by inscribing dis- sonant gender symbols on an offender, in this case, by demeaning a man with the visible signs of womanhood. Such a sentence mimicked Hall's crime of diminishing the integrity of his male identity with female garb. The sentence may also have been the justices admission that self-confessed impotence, cross-dressing, and a history of female identity compromised an individual's claims to the political and legal privileges of manhood. The court's decision that Hall should wear male attire topped by the apron and headdress of a woman seems at one level to affirm Hall's claim to a dual nature by creating a separate category for him. Yet Hall himself never expressed his hermaphroditism in this fashion, choosing instead to perform his identity serially as either male or female. The judges' man- date of a permanent hybrid identity for Hall was thus both a punishment and an unprecedented juridical response to gender ambiguity.”

In this account, a person who has operated through their life with bodily autonomy, but then when discovered by the legal system and the gossipy community of Virginia, is forced to dress in a way that signifies their mixed sex. Or their mixed gender. Hall is one of a set of people in this period, most of whom are in Europe who were studied by doctors and limited by the justice system to certain gendered fashions or to certain gendered names. Formerly, some of these people had shifted fluidly between male and female, usually a woman becoming a man. We would consider these people transgender individuals today. In the historical record, these people were often brave, adventurous, humorous, and openly desiring. They fell in love, got married, and had heartache. They switched careers and with these careers, switched genders.

Hall, when asked why they went about as a woman said they did so “to get a bit for my cat,” an openly sexual admission called “unprintable details” in the transcript you all read.

To focus on these transgender individuals bodily autonomy before being challenged by the legal system, as well as their claims of desires and of pleasure is what I would prefer to do as a historian. At the same time, the violence of the system in trying to discipline queer bodies into one or the other gender and in the strange case of Hal, into a fashion to signify mixed gender as a punishment, must also be addressed through the lens of the history of bodily autonomy.

What thoughts does the case of Hall provoke in you?

Some men don’t want to be married to someone who makes more than them. They feel like their manhood is dependent on being the person that makes more money in the relationship because their partner would be financially dependent on them. The idea that in order to be a man you have to be the dominant in a relationship is something taught by society. In movies men are depicted as physically strong, providers and emotionally stunted. Whereas a woman is depicted as emotionally open, maternal and traditionally a home maker. There are more progressive relationships that don’t dwell on societal/gender expectations. Even then there is somehow always one partner that is viewed as the masculine one.

People fear change as seen in the case of Thomas(ine) Hall. They were different and people assaulted to do examinations. It’s so heartbreaking to read about such a progressive person being treated unfairly and having to conform to society’s rules when Thomas(ine) wasn’t harming anyone. During this time people couldn’t understand how someone who they thought was a women could work out in the fields, one man even said he wanted to purchase Thomas(ine) but he first needed to know if they were a man or woman because that would determine what tasks they could do. I was surprised to read that because at this point in the story Thomas(ine) had proved they could accomplish both a man and a woman’s task well.

I really enjoyed reading about Thomas/ine Hall. I think I finally have an answer to that question everyone has most likely been asked at least once in their life: what historical figure would you want to have dinner with? I would love to hear their story from their own mouth. Although the court case includes their own testimony, the case is still heavily biased because of the judge and jury’s personal beliefs on their gender identity and societal expectations of gender. Because of these beliefs, Hall was treated as a spectacle. They became an object that was used to fulfill others’ curiosities and uphold gender roles. I find it interesting that the people around Hall were more concerned with how they would fit into their ideas of gender roles than Hall themself. I find it disgusting that Hall was forced into non-consensual searches of their body. I refuse to believe that was okay back then. There is no way that a traditional man or woman was subjected to this kind of search and I don’t think this would’ve been viewed as normal behavior. These people only saw this as fine to do because according to them, Hall was an object. Since Hall wasn’t “normal,” people believed they had the right to be curious and act upon those curiosities about Hall’s gender or lack thereof. They were treated like an animal. This kind of curiosity is still around today. Trans people everywhere are asked by complete strangers about what body parts they may or may not have when, quite frankly, is none of their business and is creepy behavior. Stories like Hall’s are not seen anymore, but the sentiments behind them are exactly the same today. For some reason, many cis people feel like they have the right to know about a trans person’s body.